| |

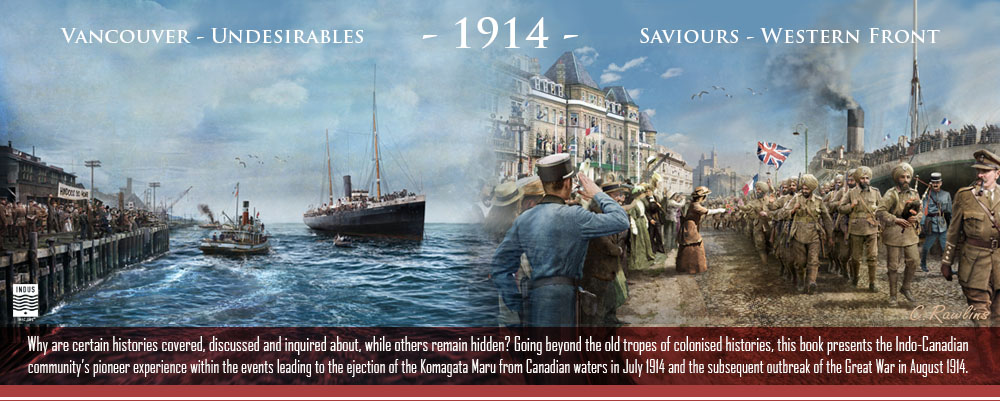

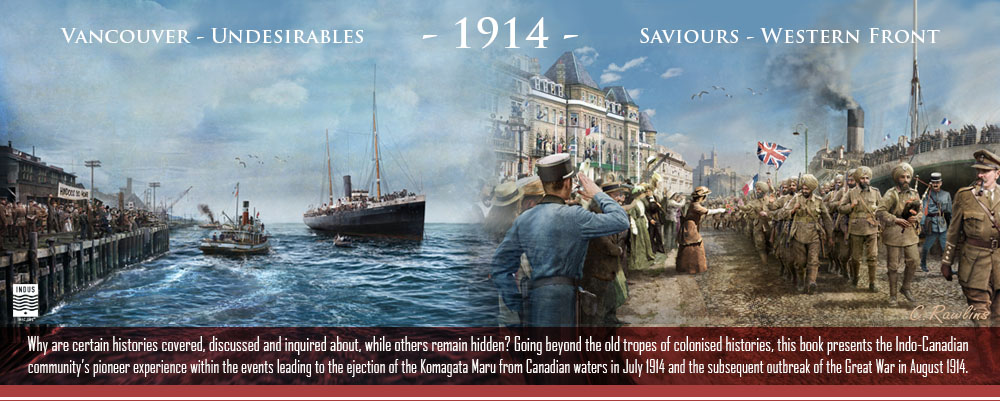

This November marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War, and as such, this Remembrance Day is perhaps the most important one in our lifetimes. It is, therefore, a fitting occasion to correct popular history's account of a critical chapter in the nation's coming of age saga. If confederation of 1867 was the birth of the country, Government policy in the shape of curriculum, citizenship guides and commemorative events, for example, has been to frame WW1, including the victory at Vimy, as a rite of passage, in which the courage and sacrifice of Canadian troops came to represent a new assertion of nationhood. After 100 years it is now time to tell a tale that has gone untold, of spurned friends coming to the aid of their Canadian brothers-in-arms during that baptism of fire on the battlefields of Europe. The protagonists in this story are the unsung heroes of the Punjab that made a critical contribution to the Allied victory in WW1.

Arriving September 26th 1914, in Marseille France, British Punjab's Lahore Division ( pre-partition India) became the first colonial force to deploy in Europe to defend liberty and freedom while millions of Europeans had yet to enlist themselves. With the fate of the Channel Ports hanging in the balance, the Indian Expeditionary Force quickly plugged the gap in the last British line of defence before Calais and thwarted the German advance forcing the opposing armies to dig in to complete a series of trenches in a stalemate that would stretch south from the Flanders coast to Switzerland. After this First Battle of Ypres, the Western Front would remain more or less static for the next 4 years until August 1918 when the Canadians were able to punch a hole in the German line during the 100 Days offensive which finally put the end of war within sight. Speaking after the war the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, Ferdinand Foch, identified the Indian Army as having delivered the war effort's first decisive steps to victory; they were critical in stemming the tide of the German invasion of Belgium and France - without their arrival in the nick of time the port of Calais would not have been saved for a Canadian landing, the Western Front would have been breached, and the British Expeditionary Force annihilated. Without them then, history may have indeed unfolded as strategised in Alfred von Schlieffen's master plan with the taking of Paris in 42 days and the war could well have been over by Christmas as many speculated at the time.

In one of history's great 'what if' moments, the ultimate Allied victory in November 1918 was put on the line in the waters of English Bay, Vancouver in 1914, two weeks before war was declared in Europe. For it was here - far from the fabled battlegrounds of Flanders - that the raising of HMCS Rainbow’s guns against British Subjects could have set the Empire ablaze - at the precise moment, covetous German minds hatched their plans for world domination. In the summer of 1914, the British Subjects being evicted from Canada as 'undesirables' were Punjabis, a community that constituted 45% of the infantry, 66% of the cavalry and 85% of the artillery of what would soon become the only battle-tested colonial army available to the Crown when war broke out.

In 1914 Canada seethed with prejudice against non-whites, and the Punjabis' status as fellow nationals presented a clear threat to a settler colonial order that deemed the coloured races to be biologically inferior and of a lower level of civilisation. The Punjabis aboard the Komagata Maru( 340 Sikhs 24 Muslims and 12 Hindus), however, saw themselves as industrious, loyal sons of Greater Britain that hailed from India, a colony whose stature had grown to that of the jewel in the Crown itself. In the early years of the 20th Century, Punjab's granaries fed the masses and its garrison was home to some of the most decorated regiments in the Empire, whose rank and file regularly paraded as the sovereign's honoured escorts at jubilees and coronations outside the hallowed halls of Westminster itself.

Arriving in Canada, a land with which they shared a monarchy, flag and common British nationality ( Canadian nationality was not enacted until 1947, the Maple leaf flag was introduced in 1965) they expected to find some semblance of kinship with their fellow British subjects. After all, the Canadian establishment had for many years used pro-Empire sentiment to help establish a Canadian identity separate from our American cousins, and by the tail end of the 19th century, 75% of the foreign-born population of Canada was British born. For these Canadians, the greatest subscription to Empire would ultimately become the 61,000 lives to be sacrificed at the altar of the world's first global war. Yet for all this, in the days before the war, Canadians could not look beyond colour as a basis for nationality and rights so would-be 'legal' immigrants from India were subjected to laws contrived to keep them out of the country on the basis of a mode of travel; then stripped of the right to vote and hold professional positions those immigrants already settled in Canada were typecast in Vancouver newspapers as undesirables - degraded, sick, hungry and a menace to women and children. Thus, on July 23rd 1914, with appeals to Canada's sense of fair play falling on deaf ears, a group of unarmed and disillusioned British Nationals were forced to relinquish their claim on the Crown for protection in one colony of the Empire as their vessel was forced at gun point to return to another. Two weeks later when war was declared, hyphenated nationalities and colour bars were at once dropped for the war effort when King George V personally beseeched the Punjabis to rally to the defence of the Crown.

Holding the balance of power in their hands, they had taken the 'King's Shilling' as volunteers, the Punjabis chose to honour their oaths; taking the high road, when it was so easy not to, they did their duty even as the Komagata Maru sailed back to India. The character and integrity of the Punjabis was tested once again 6 months later as poisonous gases wreaked havoc on a fledgling Canadian Corp in its baptism of fire in Flanders, when the call for help was made once again. On April 22nd 1915, Germany determined to take Ypres resorted to chemical weapons to shatter Allied defences. This time the Canadians stood directly in the path of the assault. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Canadians battled desperately, heroically confronting the advance in a series of bloody engagements at Mauser Ridge, Gravenstafel Ridge and at Kitchener's Wood. After 4 days of brutal fighting Allied reinforcements were despatched - and as fate would have it those 'friends in need' arriving to hold the Canadian line were the Jalandhar and Ferozepur brigades of the Lahore Division. These regiments hailed from the heartland of the Sikhs and comprised the exact same community aboard the Komagata Maru. In fact, by war's end of the 498, 560 Punjabis that served in WW1, 300,000 sons of empire put aside their grievances and enlisted directly from the districts of those aboard the evicted ship to shoulder an equal burden of war and win Dominion Status for India and equality with Canada within the Empire.

This Second Battle of Ypres marked a pivotal point in Canada's nation-building myth as it was arguably Canada's most significant battle; it 'created' the Canadian Army setting the tenor, the style and the esprit de corps of a fearsome reputation that would carry Canadian troops through the subsequent campaigns of WW1 on the road to Vimy. Many of these battles would again feature Punjabi troops fighting alongside Canadians as at Festubert 1915, Somme 1916, Vimy 1917, Cambria 1917 and Passchendaele 1917. All told, across the various theatres of war, India deployed as many men in the war effort as all the Crown's white colonies put together. Ultimately more than 74,000 South Asians were killed in WW1; Indian casualties on the Western Front are buried or commemorated alongside Canadians in 115 cemeteries in France and Belgium.

Lest We Forget on this Remembrance Day, 100 years on, we should honour all soldiers of the King that fought in 'The Great War for Civilisation', and made the ultimate sacrifice for the freedoms and democracy we all enjoy today in Canada. The all-volunteer Indian army upheld the Izzat (honour) of India on a global stage; they stood tall as friends in need at the darkest hour winning more than 9,000 awards for gallantry (including 11 Victoria Crosses). This is a shared history between the mainstream and the Indo-Canadian minority. It is an untold story of diverse communities coming together with a common goal; it is a dialogue around the ties that bind and the shared values of courage, integrity and selfless sacrifice. This is a common heritage that confronts divisive voices, it is a foundation for a shared future within a multicultural Canada.

|

|